Chuck Griffin

Chuck Griffin: Number One On The Planet Earth

Chuck Griffin was a giant among men but also a man of the people. In the 45 years that I’ve been blessed to know Chuck Griffin, he unselfishly devoted his life to making a societal change in a world that all too often changes begrudgingly. He was a visionary, community leader, activist, administrator, coach, mentor, father figure, actor, songwriter, and friend. Through the years, Chuck’s influence and impact would expand much further than East Harlem’s borders. His accomplishments and deeds developed a generation of young black and Latino youth that now continue his legacy globally.

Chuck was a child of the Jim Crow South. Born in Mississippi, it became apparent at a very early age that Chuck’s dreams and ambitions were in direct contravention of the limitations that the South placed on black men and women at the time. After being threatened by the Klan, Chuck moved to Chicago with his family that had previously migrated from Mississippi. Soon thereafter, he enlisted and spent several years in the Navy.

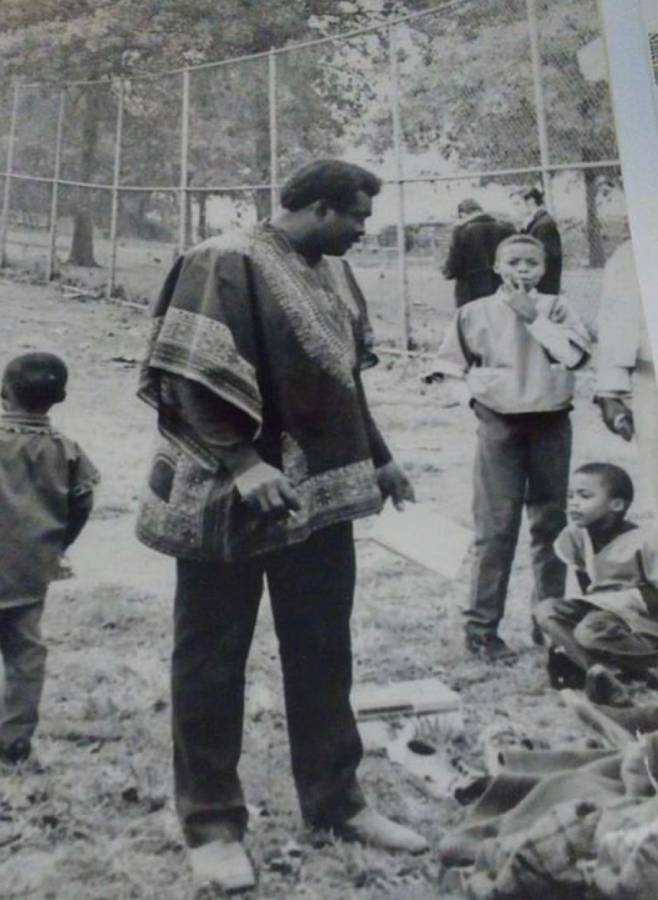

In the fall of 1967, Chuck would make the first significant step towards creating an organization that would guide and influence thousands of inner-city youth. That fall, Chuck walked through the projects (Jefferson, Johnson, Taft, Foster, and Wagner) and barrios of East Harlem like a poncho wearing Pied Piper enlisting young boys for his football team and young girls for the cheerleading squad. These young boys and girls would become pioneers for an organization that would expand its influence and impact throughout New York City’s five boroughs. In previous years Chuck had coached basketball, “the city game” with a roster that reads like a Who’s Who list of basketball legends (Herman Helicopter Knowlings, Pee-Wee Kirkland, and The Destroyer- Joe Hammond).

Despite his success in coaching basketball, Chuck chose to introduce football to Harlem for several reasons. Chuck believed football gave our youth to develop leadership and analytical skills, teamwork and trust, and a positive release for our boundless energy. More often than not, Basketball was about stars; success in football is always based on teams.

Chuck’s initial efforts were performed from the Jefferson Community Center located on 113th St. First Avenue, the three-bedroom apartment of Chuck Griffin, and the Jefferson Park football field we called the “Dust Bowl” because it had more rocks and pebbles and blades of grass. Chuck’s vision was simple; initially, he would use sports to promote education and exploration to the neighborhood’s youth. Football would be the vehicle that he used to develop young minds and leadership skills. Football was fairly new in Harlem and was very expensive to support. His partnership with Carl Nesfield, legendary Harlem photographer, Journalist, and dedicated youth worker, started a fledgling football league called the Buddy Young Football League introduced hundreds of children to the sport. The football team’s name would be the East Harlem Chargers, and they would be the foundation for what would be one of the most successful community programs in New York City.

By 1968 Chuck’s vision and the number of youth participating in the football and cheerleading programs rendered the current facilities inadequate. Chuck visualized a community center, which offered diverse and heretofore unknown opportunities for our youth to discover and explore their potential. In 1968 Chuck formed the Board of Directors to create the East Harlem Federation Youth Association (EHFYA). This was a critical period in our country due to the success of the civil rights movement. Chuck’s acuity convinced him that it was time to establish and institutionalize the gains earned through the tireless efforts of many in the civil rights movement. His mantra for every child that participated was, “there are no limitations, only barriers to be climbed or eliminated.” Chuck’s vision for the East Harlem Federation Youth Association was expansionary and introduced them to worlds they knew very little about it at all. Drawing on his own childhood growing up in Mississippi, Chuck wanted to focus on providing exciting and engaging activities that would attract large numbers of youngsters, which would motivate them to be successful in school and life.

With the full support of his Board of Directors, which included prominent East Harlemites like Stormy Bond and Berlin Kelly, Chuck set forth to find funding for his center and a home for East Harlem Federation Youth Association. Due to timing and/or providence, it just so happened that a supermarket had closed on Second Avenue between 115th and 116th streets. Chuck immediately realized the great potential that this location offered as a home for his center. The next challenge was to find funding for the purchase and renovation of this property. Chuck and the board wrote and submitted successful proposals to the Astor and Ford foundations to purchase and renovate the abandoned supermarket. Chuck was also able to convince the New York City human resources administration to furnish salaries for staff to conduct programs and activities.

The first two years in their new home, Chuck established that the EHFYA would be unlike any other community development program in Harlem. Chuck would develop five different football teams that fielded youth from ages 8 to 18. Each team had their accompanying age-appropriate team cheerleaders. Chuck and his volunteer coaches developed a juggernaut that dominated each of their divisions. This dominance was recorded on a banner that spanned 50 feet that read “Chargers Number One On The Planet Earth!” By 1971 EHFYA consisted of 500 young participants and legions of supporters in the community. In addition to the football program, Chuck instituted programs, which taught children how to play chess competitively, tutoring, and creative arts.

One of the most impactful decisions that Chuck made during this period was to arrange football games between the East Harlem Chargers and prestigious preparatory schools throughout the Northeast, such as the Hotchkiss School, the Andover School, Salisbury School, and Munson Academy. Two of our most accomplished and revered alumni had already received scholarships to The Hotchkiss School, and Chuck arranged a game against them that ultimately would be deemed a classic. The Chargers lost a one-point game to Hotchkiss, led by our former star quarterback Dennis Watlington and running back Noel Velasquez. The irony in all this was that Chuck would always complain about professional and collegiate football’s institutionalized racism that barred black athletes from being quarterbacks, and here was a young man that he developed, crushing that stereotypical myth by leading an all-white football team to victory. More importantly, this game opened up additional opportunities for our young boys to attend a number of these prestigious schools. Chuck would later parlay his engagement with the preparatory schools into a relationship that would result in supplying 25 young boys with scholarships and the opportunity of a lifetime.

Until 1971, the program’s activities took place in a large first floor open space. That would soon change. He had secured funding to do a major renovation of the center. One of Chuck’s more important decisions, which evidenced that he was a visionary, was his decision to ensure that any renovation contract would be awarded to a black or minority-owned construction company. The newly renovated center was unlike any other facility that existed in Harlem. For that matter, probably unlike any, that existed in New York City. “Chuck’s Center,” as it became known affectionately, had spread word of its success and influence throughout the five boroughs. Approximately 25 percent of our participants resided outside of greater Harlem. The center was now a multi-use facility with a library, classrooms, locker rooms and showers, photography and darkroom, archery lane, and a space for the world-renowned Voices of East Harlem to rehearse.

The early 1970s were a difficult time for community development and outreach programs. Despite these challenges, EHFYA continued its success with occasional grants and dedicated support of parents in the community. The community’s support was the result of Chuck’s unwavering dedication to the children of the community. He became viewed as one of the strongest community leaders and activists in New York City not only because of his successful youth advocacy but also in large part because of the pivotal role which he played in the struggle to empower East Harlem residents to control the schools in their neighborhoods.

In 1968 two experimental school districts were established. The more famous of the two was in Ocean Hill Brownsville, Brooklyn and the second was Intermediate School 201 on 128th Street and Madison Avenue. These two schools became the eye of the storm in our efforts to decentralize control of the schools in our communities. Chuck felt passionate about the need for communities of color to manage the schools in our communities. He was an extremely effective community organizer and helped to rally thousands of residents to make their voices heard through protests and civil disobedience. In the front lines, Chuck linked arm to arm with other brave men and women who stood up for community control of our schools.

Chuck’s involvement in IS 201 established his role as a well-known and influential community leader. He now had access to significant politicians and leaders like Percy Sutton (Manhattan Borough President), Jesse Gray (New York Assemblyman), Charles Rangel (Congressman), and Livingston Wingate (Executive Director of the New York Urban League). Many of these politicians and leaders reached out to Chuck for his support because he was a man of conviction who had the capacity to motivate our community’s members. These valuable relationships would allow EHFYA to continue through the early 1980s despite the diminishing support from the City of New York and philanthropic foundations.

Undeterred, Chuck and the Center’s pursuits of excellence expanded into other areas. The Voices of East Harlem (VOH) had developed into an internationally acclaimed group that performed in groundbreaking events such as Soul To Soul in Ghana, which also featured Wilson Pickett, Santana, Roberta Flack, and The Staple Singers. The group also recorded three successful albums and shared their inspirational sound in venues as diverse as The Fillmore East with Jimi Hendrix to Sing Sing Prison’s confines. One of Chuck’s many talents was writing music, and among the songs he wrote for VOH was a song called Right On Be Free. It was used for one of the major dance productions by Alvin Ailey, starring Judith Jamison.

Chuck’s talents were numerous and fueled by his love for archery he introduced it to Harlem, and his efforts resulted in the development of two world-class archers, Stephen Brown and Cindy Williams. Cindy was several points short of representing the United States in the Olympics. Chuck was fond of saying, “I live in the northland, and nobody lives north of me.” These were beliefs that he instilled in each one of us.

Out of all the incredible things that Chuck has accomplished in his lifetime, I truly believe that his greatest legacy is a living, breathing legacy. His legacy remains on the street corners of Harlem and has spread to places as distant as Australia. To know Chuck Griffin means that the man has touched you. One of the most important things that Chuck ever taught me was how to dream, but dream with my eyes wide open. He told us and, more importantly, showed us that we could be anything we really wanted to be and be the best at it. Chuck believed in us oftentimes when we didn’t necessarily believe in ourselves. He taught us to be fearless in the face of adversity and how to learn from experiencing defeat. Most importantly, he taught a generation how to dream but dream with eyes wide open.

I also think back on all those years that Chuck ruled with an iron fist and “The Iron Lady” and realized that at that moment, we thought he was just preparing us for a football, basketball, or baseball game. But, it dawned on me as I got older that he was investing that time to prepare us for life. Chuck introduced us to worlds that many people are not even aware exist. He introduced us to archery and produced world-class archers. He pushed us to learn how to play chess to instill confidence in our capacity to outthink another person. Chuck spearheaded a world-renowned musical group known as “The Voices of East Harlem” and made an immeasurable global contribution to the reality that “Black truly is Beautiful.” Chuck was a renaissance man that showed his interests had no boundaries, and he believed neither should ours. Does anyone remember when Chuck introduced falconry to Harlem?

You see, Chuck was an incredible force. Actually, he was a counterforce, a counterforce to all of the negative and limiting stereotypes that exist about black and Latino children. He showed us how to tell the world that we are full participants in society’s global fabric and that we are a force to be reckoned with. Chuck said, “We’re making young men and women better men and women so they could deal with all men and women. Consequently, this will make a better world.” That is the message that we must continue to teach and share with our children so that they, too, will be able to “dream with their eyes wide open.” That is why we feel passionate that naming the corner of East 115th Street and Second Avenue in honor of Herbert “Chuck” Griffin would be appropriate to commemorate the accomplishments and dedication of a truly great human being by any standards.

Calvin T. Watlington

Views: 564